Where to invest in a world on fire

Stocks are tanking, crypto's down, and startups are in an AI bubble. Where are the safe havens in a crumbling world?

My grandmother never learned how to mend clothes, a rare skill gap in mid-20th century China under Mao.

Surrounded by servants and private tutors as a girl in Szechuan province, her hands were never meant to perform manual labor. Her father, a salt baron in 1930s China, was so wealthy that he owned a private plane. He had also established one of the first banks in his region to accommodate his booming business. In the late 1940s, when the Communist victory was imminent, my great-grandfather made a calculated decision: he "donated" his private plane to the revolutionary war effort and signed his wealth and allegiance to the Communist Party.

This act of political adaptation spared him and his family from the persecution that haunted many wealthy industrialists of his time once Mao and his army were victorious. His family still lost all of their wealth in the nationalization that followed, but they kept their lives. As a young woman, my grandmother secured a respectable position as an accountant in a government firm where she was able to put her early math training to good use, and where soon after she met my grandfather — a poor boy from the countryside who was the eldest of eight and the first in his family to attend college, and a poster child for the Communist narrative of class advancement.

The trifecta of politics, economics and climate are everywhere in human history

I never met my great-grandfather, but his story has been on my mind lately as markets continue to reel from tariff announcements and more. In addition to tariff-driven turmoil, we’re facing an impending housing and real estate crisis, driven by climate risk and over-financialization. In the world of early stage venture, down rounds abound even as AI is up (but even there, on tenuous ground). Even crypto is down.

We’re starting to experience something that historians have long known — that political, economic and climatic instability are often a package deal:

When the Little Ice Age hit in the mid-1300s, the Vikings of Greenland were wiped out over the course of a short 150 years. The Norwegian monarchy's union with Denmark under the Kalmar Union shifted political priorities away from distant settlements, while trade with mainland Europe withered as the global economy slowed. At the same time, widespread cooling made local resources scarce and increased sea ice shortened the sailing season, sealing the colony's fate. Hauntingly, archaeological evidence suggests the last survivors resorted to eating their household pets before perishing from hunger and cold in their own homes — their bodies having been found without the basic dignity of burial.

When severe drought struck the Mayan lowlands between 750-950 CE, agricultural yields plummeted, triggering competition for dwindling resources, and causing political fragmentation among ruling elites. The elaborate trade networks that had connected urban centers frayed, and wars broke out between cities. Within just a century, a civilization that had built astronomical observatories and developed sophisticated mathematics had collapsed into fractured, impoverished villages.

For more awesome stories like these, check out one of my favorite podcasts, The Fall of Civilizations, which presents comprehensive audio documentaries designed for history nerds.

While I’m not ready to claim that we’re on the precipice of civilizational collapse — though others may argue compellingly that we are — I do know that when the political-economic-climatic trifecta strikes, there are few places to hide.

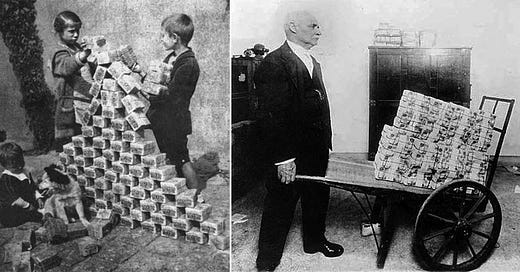

Where did the smart people hide their money during Weimar Germany?

In a more recent example that’s constrained to politics and economics, consider the fate of the German middle class during the Weimar Republic.

On the back of Germany’s humiliating loss and subsequent reparations from WWI, hyperinflation struck — hard. Between 1922 and 1923, the German mark plummeted from 160 to the dollar to 4.2 trillion to the dollar, impoverishing middle-class families who had worked and saved their entire lives. Retirees on fixed pensions became destitute overnight. Civil servants with stable government jobs, and fixed incomes, suddenly couldn't afford bread. On payday, people ran to spend their money as fast as they could because its worth could be halved the next day.

But, some people did manage to survive Weimar hyperinflation. Where did they hide their money?

We can learn a lot from the people who made out best during this time period:

Owners of productive assets like factories and farms generated essential goods that retained inherent value in spite of currency collapse.

Debtors who had borrowed money before inflation could now repay loans with (increasingly) worthless currency, basically a cheap way to eliminate debt.

Exporters who sold goods outside of Germany and received payment in foreign currency were able to shield themselves from the worst effects.

Investors who bought gold or collectibles were able to protect wealth by storing it in hard assets.

But remember that where there’s economic instability, political turmoil is right on its heels. When the Nazis rose to power a short decade later, even those who navigated economic hyperinflation well weren’t protected from destruction. First of all, if you were Jewish, your assets would have been confiscated across the board. But other types of political opponents, of which there were many, faced similar asset seizures and expropriation.

But now, climate change

And today, we have the third horseman: climate change.

The situation is worse than most realize. Recently published research by respected climate scientist James Hansen — the same researcher who first warned Congress about global warming in 1988 — reveals we've already reached +1.6°C of warming relative to pre-industrial levels, blowing past previous projections. This startling leap of +0.4°C in just two years is partly due to widespread rollout of cuts to maritime shipping emissions, which resulted in significantly less cooling (and polluting) aerosols over the oceans. Hansen’s new research suggests the IPCC has systematically underestimated both aerosol cooling effects and overall climate sensitivity — and thus has underestimated how much warming is now baked in.

At the same time, Chris Wright — a fracking company CEO who openly denies climate change as a pressing threat — has ascended to lead the DOE. It’s a dramatic reversal of the previous administration’s climate policy that, let’s be honest, was big but nonetheless not big enough anyway. Under Wright, and Trump, we’re going to produce (even more) fossil fuels, thus generating (even more) emissions and locking in (even more) warming.

Hansen warns that we now face a heightened probability of passing catastrophic tipping points like the imminent shutdown of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Current (AMOC), which regulates temperature and rainfall across Europe and North America. Hansen calls this the “point of no return” because it would lock in multiple meters of sea level rise and disrupt agriculture across dozens of countries.

While it may seem like an exercise in arranging deck chairs on the Titanic to be talking about where to invest in times of potential global collapse, in times of change, inaction is just as much of a choice as action.

So where do we go from here? Is there any safe haven that’s protective against the triple threat of economic, political and climatic instability?

Climate change will create a few short term winners — and lots of long term losers

Climate change is uneven. We know that temperatures are warming at the poles 4X faster than elsewhere and that regions already close to the precipice of unlivable drought and heat will only get dryer and hotter at accelerated rates.

Similarly, the impacts of climate change will be a patchwork of winners and losers — at least in the short term. Northern regions like parts of Canada, Russia, and Scandinavia might initially benefit from longer growing seasons and new shipping routes as Arctic ice retreats (but only so long as the AMOC holds steady, since AMOC disruption could cause freezing temperatures and death to agriculture in much of Northern Europe). Mountainous areas currently too cold for agriculture might become productive farmland as temperatures rise. But these "wins" are temporary and localized.

Meanwhile, the losers are everywhere:

The 2 billion people living in coastal cities around the world will have a tough time, no matter how stubborn their real estate markets appear today.

Regions dependent on predictable rainfall patterns for agriculture will face increasingly erratic precipitation — if they get any at all. California’s Central Valley, which produces 25% of all the food in the US, and India’s monsoon-fed farmlands, which make up 60% of India’s largely rain-fed agricultural system, are ground zero for these impacts that could ultimately affect 1.6 billion people’s food supply with these two regions alone.

The Persian Gulf, parts of South Asia and Africa and even parts of the Southern US are already approaching temperature thresholds where outdoor existence, not to mention labor, becomes physically impossible for multiple months of the year, triggering a cascade of economic, social and geopolitical changes as construction and infrastructure become harder to build and maintain, health systems undergo heat-related strains, and the region faces strategic security and military vulnerability during extreme heat periods.

So all that’s really bad. But anytime there’s a dramatically uneven distribution of outcomes, there is also a perverse opportunity for what in this case can only be called climate arbitrage.

Make no mistake: in the long run, global systemic collapse benefits no one — not even deca-billionaires in their bunkers. But in the fairly likely scenario that things don’t go full climate Terminator, there is a meaningful window to manage risk and maximize benefit as much as possible from these shifts while they're still manageable.

And the moral reason for why you should do so?

The calculus here isn't straightforward, but consider this: positioning your assets with climate awareness doesn't accelerate the crisis. Instead, it’s an important acknowledgment of reality that could help turn the tide. Those who recognize these shifts early can help build resilience where it’s possible and could end up creating entire lifeboats rather than just singular life preservers.

By contrast, climate denial (and I would categorize most of the techno-optimism you see out there as a form of denial) leaves everyone — including you — more vulnerable as reality sets in.

So what do we actually do?

How to climate-hedge across time

For those looking to protect assets against cascading risks, the timeframe matters a lot.

The next 5-10 years

In the near term, agricultural land in regions projected to gain rainfall and temperature advantages carries significant upside. Some land comes with water rights, which is important. Water rights across western North America face scarcity and have already started appreciating faster than traditional investments.

Companies specializing in climate adaptation infrastructure — things like flood barriers or advanced irrigation — are positioned for growth regardless of mitigation policies, since extreme weather caused by climate change is already happening and more is baked in.

The emerging climate havens in the northern Midwest and northern New England are already seeing an influx of early investors betting on future migration patterns.

10-20 years out

Looking further out, portable assets and flexible rights become more valuable than fixed ones. When Weimar inflation gave way to Nazi seizures, the people who made out the best were those who had international hedges. Similarly, securing residency options across multiple climate zones, if not political zones, provides economic insurance — or literally life insurance — against regional collapse.

A lot of well-off people I know are testing out New Zealand’s elusive and exclusive golden visa program. If that’s accessible to you, choose wisely. Portugal, Spain or Taiwan may not be the best places to buy $1,000,000 worth of property ten years from now. If, like for 99.9% of the population, that’s not accessible to you, read on for income-specific strategies below.

In addition to going global, think local. Investments in hyperlocal energy and food production systems insulate against supply chain disruptions (not unlike Trump ag secretary Brooke Rollins saying you should raise backyard chickens, but for real).

Similarly, people who develop medical skills, construction knowledge, or water management expertise will find themselves holding “non-transferable” assets that can't be confiscated or devalued.

20+ years out

Like many of you, I plan to still be around in 20 years and hopefully even in 40, 50 or 60. For the longest horizon, only truly resilient investments make sense, and that comes down to fundamental human needs.

The most valuable hard assets will be productive farmland in regions with stable precipitation projections and reliable water rights. Businesses providing essential services that can operate with or without increasingly fragile global supply chains will retain their value.

In this timeframe, resilience will be less about speculative technology plays and more about the businesses that matter when systems are reduced to their atomic units, such as:

Food production and preservation

Basic healthcare

Repair skills

Community-scale energy

Simplicity will prevail even as more complex enterprises falter.

Not a billionaire? Asset protection strategies for the rest of us

Unlike my great-grandfather who could donate a private plane to save his kids from manual labor via “re-education" camps, most of us are dealing with more modest means. The Thiels and the Zucks of the world may have their 5,000+ square foot megabunkers (prominent enough such that all the locals know the first place to go when food and toilet paper run short), but what about the rest of us?

Average income people — aka, most of us

For families with average means, even if big asset investments are out of reach, developing practical, applicable and tradable skills is a powerful way to hold onto value regardless of your economic system.

By learning to grow food, make basic repairs, or provide basic healthcare services, you are owning the means of production — and you can take this with you as long as you are alive.

Awhile back, I asked ChatGPT to help me come up with a list of hyperlocal, physical skills for resilience-building, and it did a good job. See that list here:

👉 Local Resilience Skill Building - A Comprehensive To-Do List

Community investments in local resilience through cooperative food systems or hyperlocal renewable energy can provide protection that individuals can’t afford alone.

There’s also domestic migration, which has historically been within reach even for the lowest income strata of society. In fact, it’s been a common move for those seeking economic opportunity.

The logistically hard but mostly financially doable act of relocating to a climate-resilient region within your current country might be the single most impactful decision you make — for example:

Moving inland from eroding coastlines

Moving away from fire

Getting closer to stable water supplies

Moderately wealthy families — high net worth but not bunker-rich

For those with significant but not stratospheric resources — like many of the successful professionals, entrepreneurs, and people with family money who own homes in expensive coastal cities today — you have more climate resilience options, but successful navigation of the coming turbulence still requires disciplined focus on what truly matters:

Geographic diversification. Like the German industrialists of the 1920s and 30s, geographic diversification is your friend, and may actually be accessible to you in a significant way. Even if you don’t qualify for New Zealand's high-threshold investor visa, you can establish footholds in multiple climate-resilient regions through small scale property ownership, extended residency permits, or even citizenship by investment programs with lower thresholds like Canada, Uruguay, Ireland or Montenegro (and its protective mountains). To be successful here, it won’t be enough just to buy property; you’ll do best by building genuine community connections and shoring up your legal rights to stay in these places.

Productive assets. In the name of portfolio diversification, it may also make sense to allocate towards productive assets that maintain value through systemic shocks— for example, agricultural land and renewable energy infrastructure in climate-advantaged regions. There’s a reason why Bill Gates’ investment group is one of the largest single private owners of farmland in the US. You may not be at Gates’ scale, but those with means can still acquire smaller-scale farms in the upper Midwest or other regions where water security is strong.

Energy independence and resilience. Finally, having a home with integrated energy redundancy (i.e., solar + storage) and water collection systems is something you can likely afford, and will definitely make use of as grid and utility instability is a near guarantee in both the near and medium term future. Instead of buying another Instagram vacation, it’s wiser to use your extra resources to buy livability through grid disruptions and extreme weather events (as my own experience showed).

You’re only as strong as your weakest neighbor, so give where you can. Hard times drive us towards scarcity mindset, but that’s actually the wrong move if you care about results. For those with means, a strategic philanthropy approach focused on local resilience where you live or have connections — like supporting community-scale food systems, hyperlocal climate adaptation, and disaster preparedness where you already are — not only builds social capital but directly strengthens the communities you depend on. Unlike the ultra-wealthy who can attempt isolation (they’ll fail eventually though), your security is tightly linked to community stability.

As a final note here, it might be time to start thinking about liquidating investments in assets at clear climate risk. For example:

Coastal real estate

Stakes in industries facing obsolescence in a climate-constrained world

Any long-term money sinks that tie up liquidity

The most successful family offices understand the importance of wealth preservation not just growth, and even if you’re not that rich, this mindset will serve you as systemic risks intensify.

Knowledge workers — a lot of us Substack readers

I want to include a special note about knowledge workers, since that describes so many readers here.

Brains with screens who are “high-earning but not rich yet (HENRY)” face a different challenge. Our skills become less valuable not just with the advent of AI but also as complex economic systems simplify.

On the positive side, some of us have advantages in geographic mobility. Remote work means you can move as conditions change, while still retaining income generation capabilities — at least for awhile. We can also build international lifelines more easily as our work and networks easily cross geographic and national bounds. Our relative economic comfort today also gives some of us at least some time surplus that we can invest in building greater skill-based resilience (see my skill menu, and choose your next hobby wisely).

Knowledge workers should be thinking hard about using our brainpower and capacity for learning to diversify our skill portfolios beyond purely digital expertise. Being a knowledge worker means you can do more than just grow food or fix an engine — you can use your study skills and internet / LLM fluency to teach yourself whole scale permaculture design or learn the workings of small-scale energy systems.

And of course, you can also save your dollars for real estate and productive assets during a time when consumption will be increasingly punished by tariffs and inflation.

To live, adapt

If you’ve never seen the 1994 epic To Live by director Zhang Yimou, I highly recommend it. It’s a dramatic, Hollywood-esque illustration of the ancient Chinese parable about the farmer's horse.

An old farmer's horse runs away, and his neighbors say, "What terrible luck!"

The farmer, being characteristically Chinese, cryptically replies, "Perhaps."

The next day, the horse returns with seven wild horses, and the neighbors exclaim, "What wonderful luck!" Again, the farmer just says, "Perhaps."

Later, the farmer's son breaks his leg trying to tame one of the wild horses. "What terrible luck!" say the neighbors. "Perhaps," answers the farmer.

Soon after, the army comes to conscript young men for a deadly war, but they pass over the son because of his broken leg. And so on it goes.

Wisdom isn't in predicting outcomes but in navigating change.

If we learn anything from circumstances as disparate as Weimar hyperinflation and my great-grandfather's journey from opulent industrialist to elderly commoner living in a concrete flat, it’s that adaptation requires a lot of letting go. My great-grandfather gave up a plane and a courtyard mansion to keep his life. The most adaptable Germans let go of physical goods in exchange for immediate necessities when money failed them.

Political, economic and climate instability will demand that we continuously let go — and indeed, this mirrors the ultimate ask that life itself makes of us.

The most resilient strategy isn't hiding assets in some mythical safe haven, because really that doesn’t exist. Instead, it’s about building the capabilities, relationships, and adaptability to spread our bets across different possible worlds so we can make it through whatever bottleneck is coming our way.

In a world of growing instability, the best investment isn’t something you can stash away — it’s something you can carry with you.

This might've been the most elegant summary of the metacrisis. The way you weaved together practical tips with higher-level lessons is seriously impressive. Thank you Susan.

From Spain, Thank you very much, Susan. What I just read from you is impressive. It's a prophetic work that describes what scientists have repeatedly announced, and what deniers reject, but which is getting closer and closer.

It's a shame, because today, what people want is to enjoy a life that is increasingly threatened by the passing day. The future is very bleak with the three threats looming over it: economic collapse, climate disaster, and universal war. No one can deny this possibility, but everyone looks the other way.

I became aware of this a long time ago, and I wrote a book for my grandchildren (who are the ones who will bear the brunt of the threat) entitled "Your Grandfather Tells You," in which I projected what their lives would be like in childhood (2020 to 2030), adolescence and youth (2030 to 2050), adulthood (2050 to 2080), and old age, if they ever reach it (2080 and beyond). The goal is to prepare them for what's to come and gain resilience.

I'm 75 today. It won't catch me by surprise, but before I move on to another life, I'm leaving things in such a way that those who follow me will already have it made. I live on the north coast, right on the beach, and I have another home also on the north Atlantic coast. I've put my houses up for sale to move inland to a house with land, which will be the one my family inherits.

I'm trying to advise my grandchildren on the decisions they need to prepare and educate themselves for adulthood, so they choose the paths that will allow them to have a better life.

The gaps between citizens are growing ever wider, and the middle classes are becoming increasingly impoverished, while the poor are deprived of the most basic needs. Migratory pressures are already causing problems in many countries. Water and food shortages are increasingly displacing more of the population. Access to survival resources will become increasingly difficult.

For all these reasons, your writing is very important. Everyone should read it, but above all, memorize it. If they do, they will be better off in a future that is already visible beyond the horizon, and you don't have to be a fortune teller to see it. Just read what you wrote.

Thank you very much, Susan, for such sincere work. I congratulate you. So far, this is the worst I've read on the subject. Greetings from Spain.

Luis Domenech