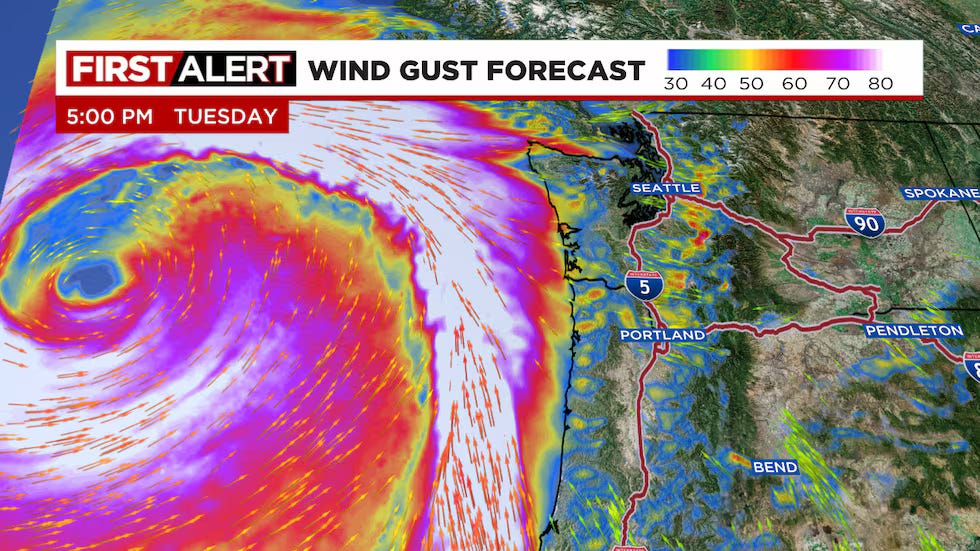

Last week, a bomb cyclone tore through Western Washington, leaving half a million people without power.

For 76 hours, we were plunged into a cold, lightless silence. Our home’s heat pump, appliances and lights all went dark. Even the nearby cell towers were affected by the blackout, so we were cut off from all but 911 (this would come in handy later).

On the second chilly night, while trying to heat milk in an attempt to maintain normalcy for my son, I managed to start a cooking fire from a faulty camp stove. Five-foot flames licked up to our ceiling as I dialed a panicked 911 call while my toddler screamed outside the front door. I somehow managed to throw the flaming stove into our sink while positioning our sprayer faucet directly above it. Firetrucks rolled up moments after the fuel and flames had burned themselves out.

I later learned that fires are common during power outages, due to the increased use of camp stoves, fireplaces and candles. We were fortunate to have a working fire station nearby and unblocked roads, but many people in more widespread disaster situations don’t have this safety net. We were shaken, but OK.

To be clear, this wasn’t Hurricane Katrina or Helene. This was wind howling through the sky that came from the wrong direction and knocked out trees and infrastructure throughout the region, but there was no flooding and very little rain at all. It was ‘just’ a blackout.

Outages will be the most common expression of climate change

In the 1980s, power outages were rare occurrences, happening some 40 to 50 times per year around the country. Today, power outages are commonplace — both more frequent and more severe. The US sees double the total number of outages that it did in 2003, when higher precision reporting standards went into effect, and also experiences more blackouts than any other developed economy. This instability is increasing with climate change.

A few recent examples:

Hurricane Ian (2022): 2.7 million people in Florida

Hurrican Ida (2021): 1 million people in Louisiana, some for more than 5 days

Winter Storm Uri (2021): 5 million people from Texas to North Dakota

Texas Freeze (2021): 11 million people in Texas

Christmas Eve Blackouts (2022): Duke Energy And Tennessee Valley authority implement their first ever preventive rolling blackouts for millions of people across the South, in order to avoid grid collapse

Earlier this year, research on climate risk from Munich RE found that 2023 saw $200 billion worth of losses from non-earthquake natural disasters, most of it concentrated in North America, and half of it uninsured. Notably, $76 billion of those losses were from thunderstorms in the US alone.

Whether it’s a hurricane, a bomb cyclone or a thunderstorm, the most common indirect or direct result is the loss of power, and unfortunately it’s about to get worse.

Even as we scramble to develop and implement grid enhancing technologies and other grid resilience measures, climate change is outpacing us. Extreme heat melts power cables, as it did during the heat dome that drove temperatures above 40 degrees Celsius in the Pacific Northwest in 2021, and hot weather also reduces generation capacity at every kind of power plant, from coal and gas to nuclear to solar and hydro.

Transmission is also disrupted: 70% of large U.S. transformers are over 25 years old, creaking under the strain of higher ambient temperatures, as well as sudden extreme cold snaps, that cause accelerated degradation of these critical grid components and lead to widespread failures like what happened during the Texas Freeze, Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico, and throughout PG&E’s territory in California.

The luxury of adaptation

Surviving 76 hours without power is easier when you have a fireplace, a car to drive to unaffected areas, and money for conveniences. We didn’t leave our home for a hotel because our outage map kept indicating that our power would be restored the next day (which became the next day and the next), but we could have. Or, if we had been even better resourced, we could have hopped onto a chartered flight to another home in a different part of the country or world, far away from the darkened traffic lights and empty store shelves of our home city.

Disaster preparedness, and adaptation itself, is a luxury.

We’ve all heard the stories of families burning furniture in Texas to survive the 2021 Freeze’s uncharacteristic temperatures, or the unfortunate individuals who died of carbon monoxide poisoning or lost access to medications like insulin that require refrigeration.

To shield against these outcomes, you might invest in a home battery ($3000 to $15,000), a standalone or home generator ($500 to $25,000), or a propane heater ($100 to $300). All this would go a long way to ensuring your home’s short term resilience — as long as you’re not one of the 45% of America that reports struggling with basic healthcare costs or the 37% of Americans who say they can’t afford an unexpected expense. But even fundamentals like flashlights, firewood and fire extinguishers require surpluses of forethought, time, and money.

On a larger scale, climate change adaptation will cost the world’s poorer nations $340 billion per year by 2030, on top of the hundreds of billions in losses most are already experiencing — and that trickles down to individuals too. New research suggests that climate change could cost individuals born today $500,000 to $1 million over their lifetimes.

So why aren’t we investing now?

Our brains are hardwired to be unprepared

There’s been a lot written about what we need to do to modernize the grid, so we won’t go into that here. Instead, I want to talk about the adage, “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure,” and why it’s so hard to live by.

We’re hardwired to prioritize immediate needs over hypothetical future scenarios. Those of us who have spent time and money on preparedness have done so because we have substantial surpluses of mindshare, money and time.

Being prepared for something that isn’t real yet doesn’t give you an immediate dopamine reward the way so many of our other activities are engineered to do, and that’s true for individuals and families all the way up to nations.

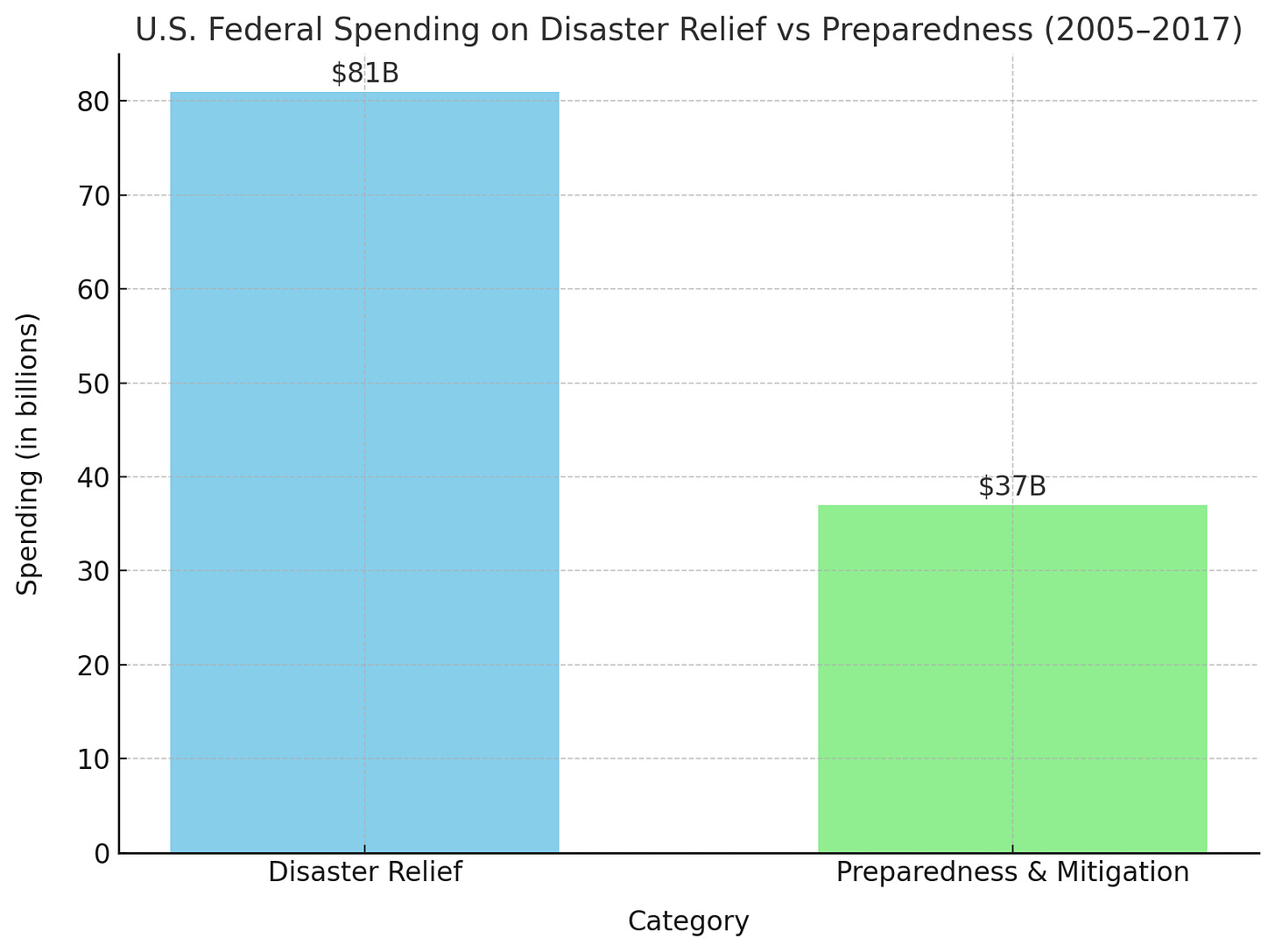

As an example, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) spent $81 billion on natural disaster relief between 2005 and 2017. In that same period, FEMA spent $37 billion on preparedness and mitigation. In other words, for every $1 spent on preparedness and mitigation, FEMA spent more than $2 on disaster relief.

But before we scoff at FEMA, how much money have you spent on preparedness?

In my house, we bought a Peloton before we bought a home battery.

Just as with climate mitigation, adaptation never feels urgent — until of course, it is.

What I wish I had done differently

The bomb cyclone was inconvenient, but for the most part, not life-threatening. But what happens when the next storm is worse, with outages that aren’t just localized but regional? What happens when power is out for weeks instead of days?

I wish I’d taken the time earlier to stockpile firewood, double-check the charge levels in all our flashlights, retest our camp stove under non-emergency circumstances. I wish I’d invested in a home battery system, like we’ve been considering for ages but have always put off. I wish I’d researched GoogleFi and other service alternatives like I kept meaning to do so I could have had access to critical communications in the first 36 hours when my carrier’s towers were down. In hindsight, all of these tasks were on my list already, but never at the top of it.

Outages are a symptom of a deep vulnerability our systems, and yet they’re also mundane and unremarkable in many ways. As climate change worsens, our great challenge is to resist the temptation to normalize its effects, or to grow complacent to an increasingly uncomfortable, unproductive and expensive future.

My hope is in that in sharing this story and others like it, we can inspire a little more frontend action to prevent backend disruption.

The next storm is coming. Will you be ready?

Susan, glad things worked out in the end. Thanks for keeping the climate resilience conversation front and center by sharing your experience. This ordeal you all went through is a stark warning of how bad and unpredictable these events can be and how they can catch us off guard on multiple fronts. To better preparedness and better times ahead..

Susan, this is such a compelling and vivid account—it’s a stark reminder of the precarious balance we rely on daily, and how easily it can tip. Your story brilliantly illustrates both the personal and systemic vulnerabilities we face in the era of climate change, as well as the quiet luxury of being prepared.

Your honesty about human nature—our tendency to prioritize the immediate over the hypothetical—is so relatable. That line about buying a Peloton before a home battery struck a chord. It’s a reminder that even those of us aware of the risks struggle to prioritize adaptation until it’s too late.