The Coming Climate Housing Crisis

Climate change is making people rethink southward migration. So why are real estate prices still up?

In a recent Barron's story that flew under the radar in climate circles, a 60-year-old Chicago attorney quietly upended decades of American retirement wisdom. Beth McCormack abandoned her plans to purchase her dream home in Florida, choosing instead to rent. Her decision wasn't driven by housing prices themselves, since she’d been saving for her Sun Belt retirement for years. Instead, McCormack was ultimately dissuaded by the skyrocketing — and volatile — cost of insurance.

Flipping the script on decades of American lore about the dream of home ownership, McCormack said the biggest draws were the lower cost of renting and “just closing the door at the end of the rental time.”

McKormack’s story signals the beginning of a restructuring. How Americans relate to housing as climate change claims growing territory is about to permanently transform affordability, ownership, and wealth creation.

The Great Migration — flipped

For generations, the story of American retirement has followed a predictable geographic script: spend your career and family years in colder northern states, then cash out and head south for golden years of sunshine and lower costs of living. This snow-to-sun migration pattern has shaped entire state economies and driven decades of development across the southern third of the United States.

All that is now unraveling.

A recent study from the San Francisco Federal Reserve found that the perennial migration from Snow Belt to Sun Belt has not only slowed over the course of recent decades but is likely reversing entirely, particularly among college-educated cohorts who have the resources to make climate-informed decisions.

The researchers are clear as to the cause:

"Given climate change projections for coming decades of increasing extreme heat in the hottest U.S. counties and decreasing extreme cold in the coldest counties, our findings suggest the 'pivoting' in the U.S. climate-migration correlation over the past 50 years is likely to continue, leading to a reversal of the 20th century snow belt to sun belt migration pattern."

From “Snow Belt to Sun Belt Migration: End of an Era?”, by Sylvain Leduc and Daniel J. Wilson, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco

This reverse migration trend is reshaping economies across all 18 states of America's Sun Belt, but nowhere are the stakes higher than in Florida (and Texas, and California) where the real estate sector dominates state GDP.

Where real estate is your economic powerhouse

Here's where the story gets complicated — and even more concerning. Despite mounting climate risks, the real estate market in Sun Belt states hasn't collapsed. To the contrary, it has grown as a share of economic output in many climate-vulnerable regions. 12 of the 15 fastest-growing cities in the U.S. are in the Sun Belt, according to the US Census.

In Florida, real estate is the single largest sector of the state economy, ahead of even tourism. It accounts for nearly a quarter (24.1%) of total economic contributions, and includes everything from real estate transactions, to construction, to consumer expenditures related to home purchasing and ownership.

Florida’s economic reliance on real estate has deepened consistently over decades.

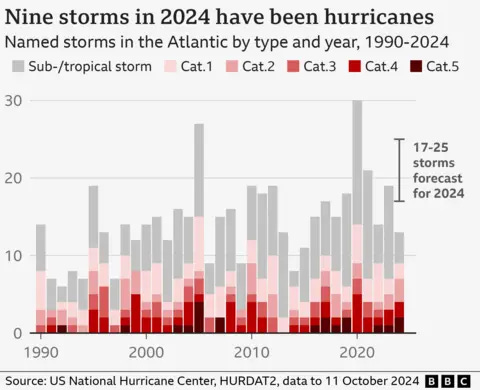

This is in spite of a steady increase in both the frequency and the severity of Atlantic hurricanes over the same time period.

Other Sun Belt state economies show a similar dependency:

Real estate makes up 23.1% of Arizona's GDP, and as a share of the overall state economy grew more than any other sector.

The sector makes up 17.6% of California's enormous economy, which features other competing titans such as tech, aerospace and healthcare. Real estate’s contribution to California’s GDP totaled $680 million in 2023.

In Texas, real estate ranks as the second-largest contributor to GDP, and in 2023 exceeded oil and gas extraction by more than $100 billion.

All percentage figures from the National Association of Realtors.

Nationwide, real estate contributed $4.9 trillion to GDP in 2023—approximately 18% of the entire U.S. economy. This isn't just about vacation homes; real estate forms the fundamental structure of American wealth creation and economic stability.

But that doesn’t mean it’s a sound foundation.

A recent study in Nature Climate Change found that residential properties in the US that were exposed to flood risk, as is the case across the southern Gulf states, were overvalued by $121 to $237 billion, or by around 8.5% above their true current value. Even more concerning, the study says that the persistent overvaluing of coastal properties is likely perpetuating perverse incentives leading to continued development in climate risk zones and underinvestment in risk mitigation — creating an overall climate risk-driven housing bubble.

So real estate is a primary economic driver across the climate-beaten Sun Belt, but it’s also very likely a bubble. Before we get to what this means for the broader financial system, let’s talk about how all of these dynamics are actually helping some people and entities get richer — echoing both MAGA politicians and Rhett Butler who said:

“There's just as much money to be made in the wreck of a civilization as in the upbuilding of one.”

— “Rhett Butler,” in Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell

Climate risk and the gambling dynamics that favor elites and institutions

So if climate risks are mounting, why hasn't the real estate market in these regions already collapsed?

The answer lies in who's buying, how they're financing their purchases, and how risk is being redistributed — and it starts with mortgages and insurance.

When the average American is ready to buy a home, their first step is to get pre-approved for a mortgage. Most mortgages require home insurance: conventional mortgages from banks, credit unions, and traditional lenders almost universally require homeowners insurance as a condition of the loan, and FHA, VA, and other government-backed loans all require insurance coverage too. As insurance premiums go up, become unpredictable year to year, or become unavailable as has been the case throughout large swaths of California, they’ve increasingly become the bottleneck to home affordability and ownership.

However, there is one way around this bottleneck, and it’s the same trick that works for a lot of things these days: having a lot of money.

No insurance, no mortgage, no problem

Shortly after All State and State Farm announced they would cease to service existing policies or write new ones in California, a friend told me about finding their dream home in the state. In the high 7-figure range, it was a ‘steal’ for its location, features and size for this particular family of a successful entrepreneur. It was also an example of how the evolving interplay of climate change and insurance are changing the cost of home buying, and who is now able to buy.

As climate risks intensify and insurers are either withdrawing coverage entirely from high-risk areas, dramatically increasing premiums, or reducing coverage, buying a home has gone from a middle class staple to a signal of wealth and access, reserved for deep-pocketed all-cash buyers and institutions.

What happens if you want to buy a home in a region where major insurers are no longer writing premiums, and you’re not rich?

In California, your options are:

The California FAIR Plan. This is California's insurer of last resort, a state-mandated association that provides basic fire insurance to homeowners who can't otherwise obtain a policy, with limited coverage and higher prices than traditional policies.

Lender-placed insurance, where mortgage companies force-place high-cost policies that protect only the lender's interest, not the homeowner's equity.

Smaller specialty insurers that offer policies at much higher prices.

We hear a lot about California, but it’s happening elsewhere throughout the Climate Risk Belt too. In Florida, the average annual homeowner's insurance premium for $300,000 of coverage has reached $5,488 — more than double the national average of $2,258. These averages actually mask the more extreme cases: one homeowner near Fort Lauderdale saw her premium jump from $8,950 to $18,500 in a single year, despite never having filed a claim.

The insurance crisis hasn't completely halted the mortgage market in California, but it has dramatically increased costs and barriers to entry for many buyers, and created a competitive advantage for a specific profile of buyer.

When insurance becomes unaffordable or unavailable, three things happen:

Traditional mortgage-backed homeownership becomes impossible for average earners;

Cash buyers (predominantly wealthy individuals and investment firms) gain enormous advantages;

The rental market expands as the only viable option for many residents.

This creates a crisis of affordability and access that is mediated through insurance markets rather than through direct housing prices — concentrating not only wealth but also the historical means of wealth generation, in fewer and fewer hands.

On his podcast with Kara Swisher, high net worth businessman Scott Galloway has frequently noted how this advantages the already rich. He can buy his beachfront Florida home in cash, forego insurance entirely and save on premiums until disaster strikes, if it ever does. In the years that it doesn’t, he’s generating rental income for minimal cost, and if the seas do come to flatten his property, it’s a loss he can afford to take.

Institutional investors apply this same principle at scale. Large institutions take on climate-vulnerable real estate the way high rollers approach a casino:

They diversify across geographic regions, ensuring no single disaster can ruin them

They maintain sufficient capital reserves to weather temporary losses

They access sophisticated financial instruments to hedge specific risks

They leverage superior data and analytics inaccessible to retail buyers when making investment decisions

They can self-insure or access specialized reinsurance markets unavailable to individuals

Why the house always wins eventually

In gambling theory, these advantages help increase the odds of long-term success despite short-term volatility — and it’s a big part of the reason the house always wins eventually.

The same principles apply to climate-vulnerable real estate.

Individual homeowners typically concentrate 60-80% of their net worth in a single property in a single location. They can't diversify, can't self-insure, can't access sophisticated hedging strategies and don’t have access to any special information. Critically, they can't absorb even a single major loss without financial devastation.

This mathematical advantage explains why institutional investment in single-family homes has accelerated precisely as climate risks intensify.

Blackstone, Invitation Homes, American Homes 4 Rent, and other major investors have grown their holdings in Florida, Texas, Georgia, and other climate-vulnerable states not because they’re climate deniers who don’t understand risk, but precisely because they understand it so very well.

These are structural advantages that drive asset aggregation for institutional holders in an increasingly volatile market.

Climate change is short-circuiting the path to the American middle class

For decades, homeownership has been the primary vehicle for middle-class wealth building in America. Buy a home with a mortgage, build equity through payments and appreciation, and eventually own an asset that provides housing security in retirement while potentially passing value to the next generation.

Climate change short-circuits this process by making insurance—a requirement for mortgage lending—either prohibitively expensive or entirely unavailable in growing regions of the country. This doesn't make housing disappear; it simply changes who can own it.

Institutional investors and high net worth individuals, who can purchase properties without mortgages or self-insure against risks, step in to buy properties that average Americans can no longer finance. These properties are then converted to rentals, ensuring continued cash flow while transferring the risk of catastrophic loss to the institutional balance sheet.

How it works in practice:

Traditional homeowners build equity with each mortgage payment

Renters build nothing, while their payments build someone else's equity

Over a lifetime, this gap compounds into hundreds of thousands or millions in wealth difference

This isn't a temporary market fluctuation but rather a structural transformation that permanently disadvantages non-owners. And because existing homeowners in high-risk areas confront the same insurance pressures when they sell, many are forced to accept discounted offers from cash buyers who don't face the same constraints.

The financialization of climate risk is building a house of cards

The insurance bottleneck doesn't just shift properties from individual to institutional ownership. It’s also spawning an entire shadow financial system that turns climate disasters into tradable commodities.

As traditional insurers retreat from high-risk regions, Wall Street smells opportunity. Financial firms have created new products like catastrophe bonds, weather derivatives, and climate-disaster swaps designed to repackage climate risk. These instruments reached a market size of over $40 billion in 2023, with issuance growing 33% since 2019 alone. This financialization of risk enables sophisticated investors to place targeted bets on specific climate outcomes while creating the illusion of distributed risk.

Here’s how the mechanics of a typical catastrophe bond work:

Insurance company XYZ creates a special purpose vehicle that issues bonds to investors

The investors receive attractive yields (often 5-15% above treasury rates) as long as a specified disaster — like Category 4 hurricane hitting Miami — doesn't occur during the bond term

If the disaster does happen, investors lose some or all of their principal, which goes towards paying insurance claims

How the house of cards tumbles

In theory, these products could help manage systemic risk by spreading it across global capital markets, but in practice, they concentrate benefits among sophisticated players while potentially hiding systemic vulnerabilities.

Institutional players are able to aggregate their advantage from climate risk financialization in five ways:

Access barriers and high buy-in: Catastrophe bonds, and many of these other products, are only available to qualified institutional buyers with minimum investments of $250K to $1M buy-in minimums.

Information asymmetry: Like all financial firms, the ones structuring these products have an analytic advantage via access to proprietary climate models, historical loss data, and risk assessment tools that most investors don't see.

Technical complexity: Understanding catastrophe bonds requires specialized knowledge, typically concentrated in a small number of firms, of both insurance mechanics and complex financial structures.

Fee harvesting: Investment banks, modeling agencies, and structuring agents extract fees ( 2-4%) at every stage of instrument creation and trading creating and trading these instruments, getting paid for their work regardless of outcomes.

Regulatory arbitrage: Instruments are commonly domiciled in offshore jurisdictions (Bermuda, Cayman Islands) with less regulatory oversight.

At the same time, these products are hiding a cascade of systemic vulnerabilities:

They underestimate risk correlation. While marketed as "uncorrelated" with traditional investments, in reality extreme climate events can trigger related failures across multiple instruments simultaneously.

They all use the same models. The entire pricing structure depends on climate models that might be… wrong. Or at least might be dramatically underestimating tail risks in a rapidly changing climate.

They obscure who owns what and who your counterparties are. It becomes virtually impossible to track who ultimately holds what risk after these instruments are traded, repackaged, and used as collateral for other investments.

They layer leverage in scary ways. These instruments also often involve multiple layers of leverage, where the actual risk exposure ends up being much bigger than the original amount at stake (Do mortgage-backed securities ring a bell?)

Everyone’s selling to each other and themselves. Insurance companies issue cat bonds, but also rely on reinsurers who themselves issue cat bonds. This creates a circular pattern that further layers risk onto risk.

In January 2022, Allstate issued a $500 million cat bond to cover hurricane losses in Texas. Six months later, Florida's Citizens Property Insurance Corporation issued a record-breaking $1.5 billion catastrophe bond. These investments are backed by major pension funds, endowments, and hedge funds — all attracted by returns that supposedly aren't correlated with broader market movements.

There’s just one problem.

Everything hinges on climate models that are increasingly unreliable — and underestimate true risk — in a climate-changed world.

When NOAA's critical climate data becomes politicized or inaccessible, as it has under the current administration, these mathematical models lose their foundation, and investors (and their investors) lose their shirts.

Worse than mortgage-backed securities

There’s one key way that this might be even worse than 2008. In the mortgage-backed securities crisis, the underlying assets — the houses people financed — remained physically intact despite their financial devaluation. There was still something standing at the end of the day.

In a climate-changed future though, the physical assets themselves may be destroyed, eliminating the possibility of market recovery through asset stabilization. A submerged coastal development can't be "rescued" by government intervention; it's just gone.

This house of cards isn’t just about financial markets. It undermines the foundation of property ownership in climate-vulnerable regions, and has consequences for housing markets across the country.

The climate crisis is a housing crisis

We've gotten used to thinking about housing affordability as a supply-and-demand problem solvable through more construction. Just build more homes, remove regulations, increase density and all will be solved! This 2000s era urbanist view collapses in the face of climate reality.

We can build all the houses we want in Florida’s coastal wetlands or California’s fire-prone mountains, but if no one can insure them at reasonable costs, they will remain out of reach to everyday buyers no matter their purchase price. And more of that upside — and risk — will get concentrated on the ledgers of the institutions that already own and govern so much of American life.

This is a climate housing crisis hiding in plain sight. It doesn't play by the same rules as your bread-and-butter affordability troubles, but it delivers the same result: ordinary people increasingly locked out of the ownership class, against the backdrop of a steady transfer of economic power from individuals to institutions, from the many to the few.

Without intervention and adaptation, we face a future where climate change doesn't just erode our coastlines and landscapes, but also triggers a cascade of crises — threatening not just our ecology but also our systems of wealth creation and the foundations of our financial architecture.

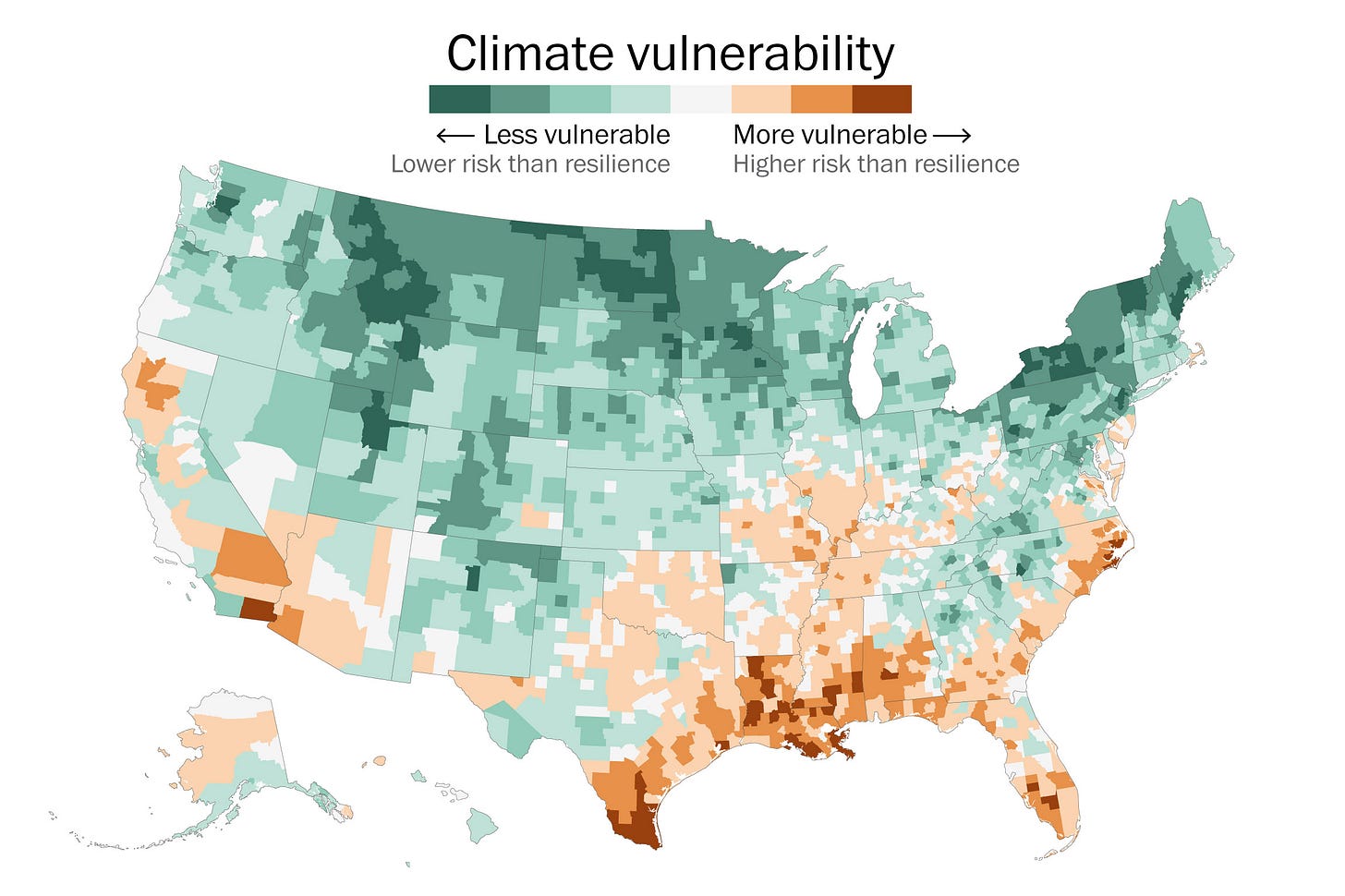

Over the next few posts, I’ll be exploring themes of adaptation and resilience to look at how baked-in climate change interacts with where and how we live, starting with my next post on “lifeboat regions” and thriving in a climate changed world.

Reminds me of this video that went viral on IG a few weeks ago: https://www.instagram.com/p/DGQvRHkPOuX/

Come on up to the Great Lakes states, baby!

Amazing piece, Susan!